Prairie Fire: The Ballad of Deadwood Dick

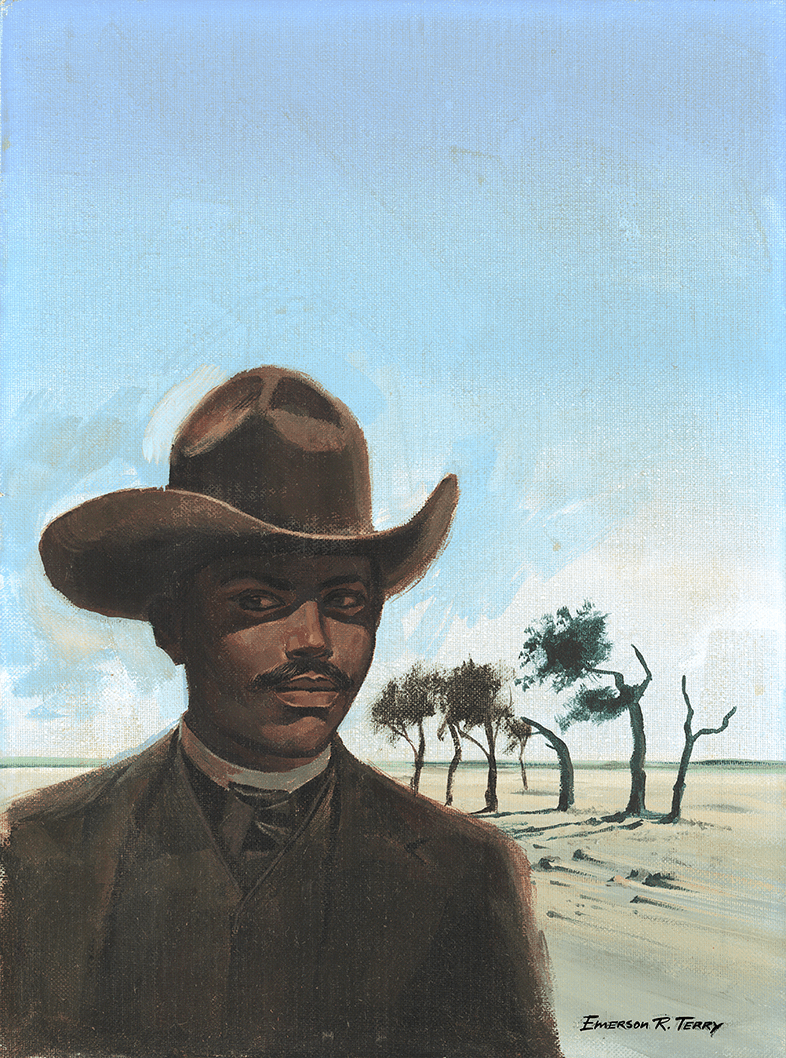

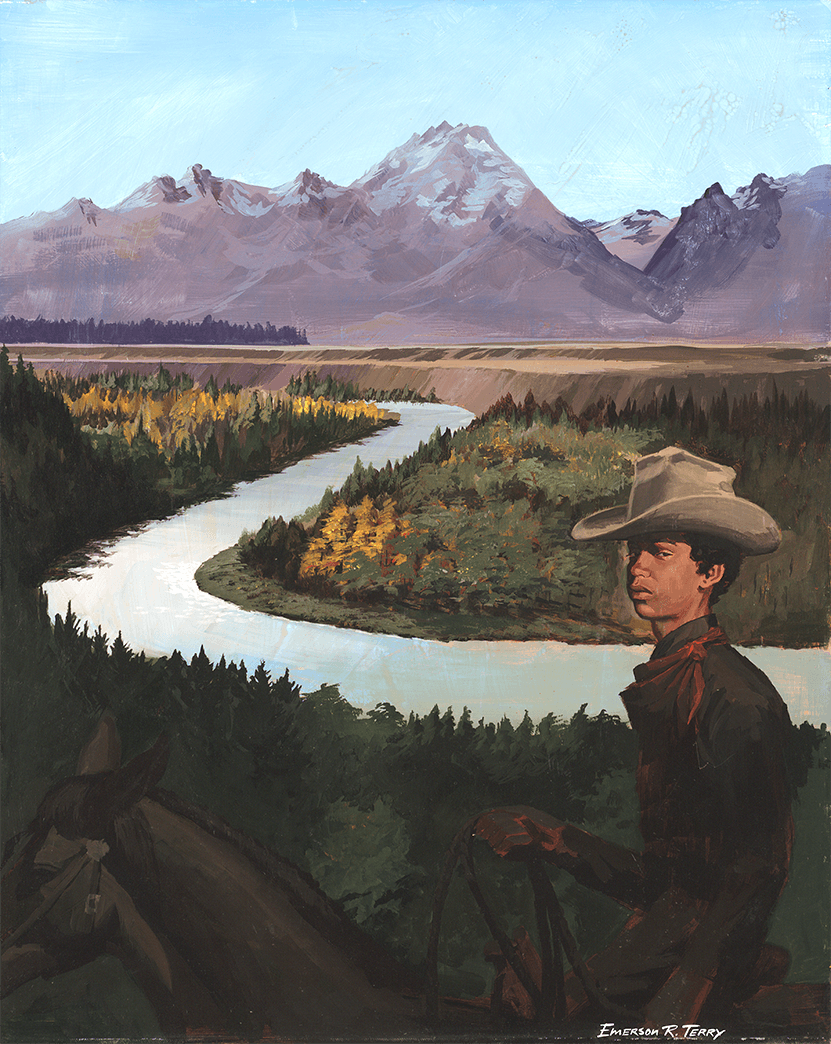

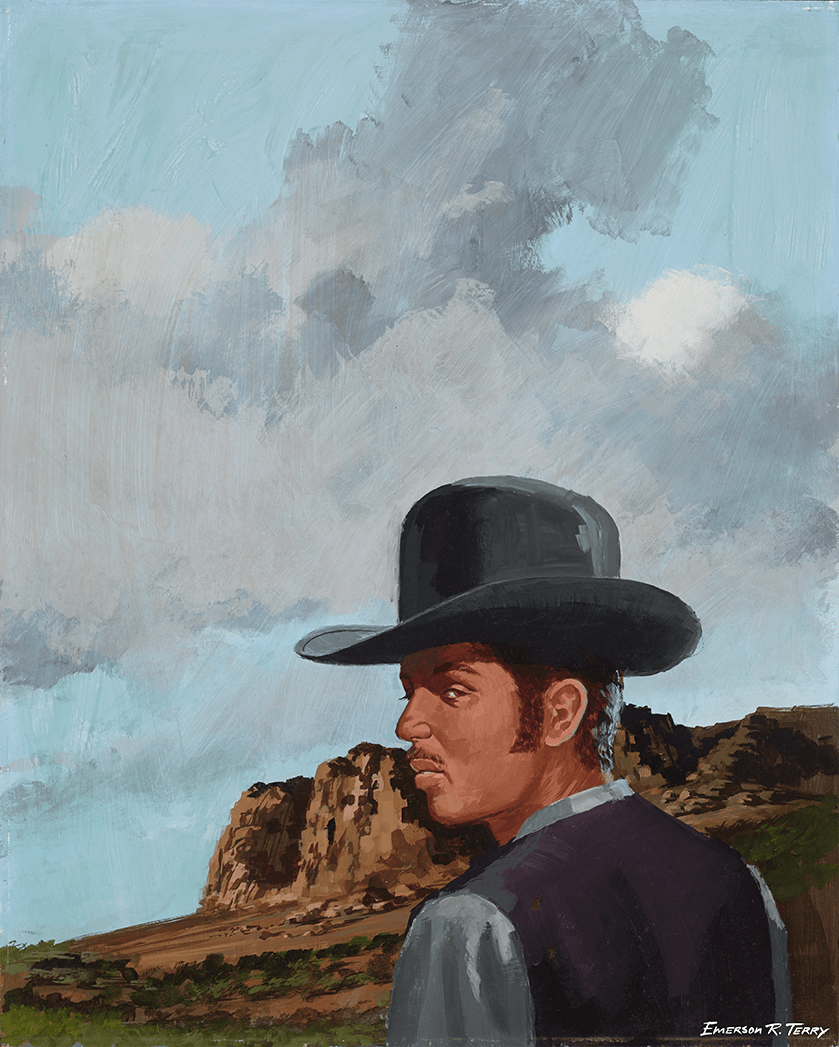

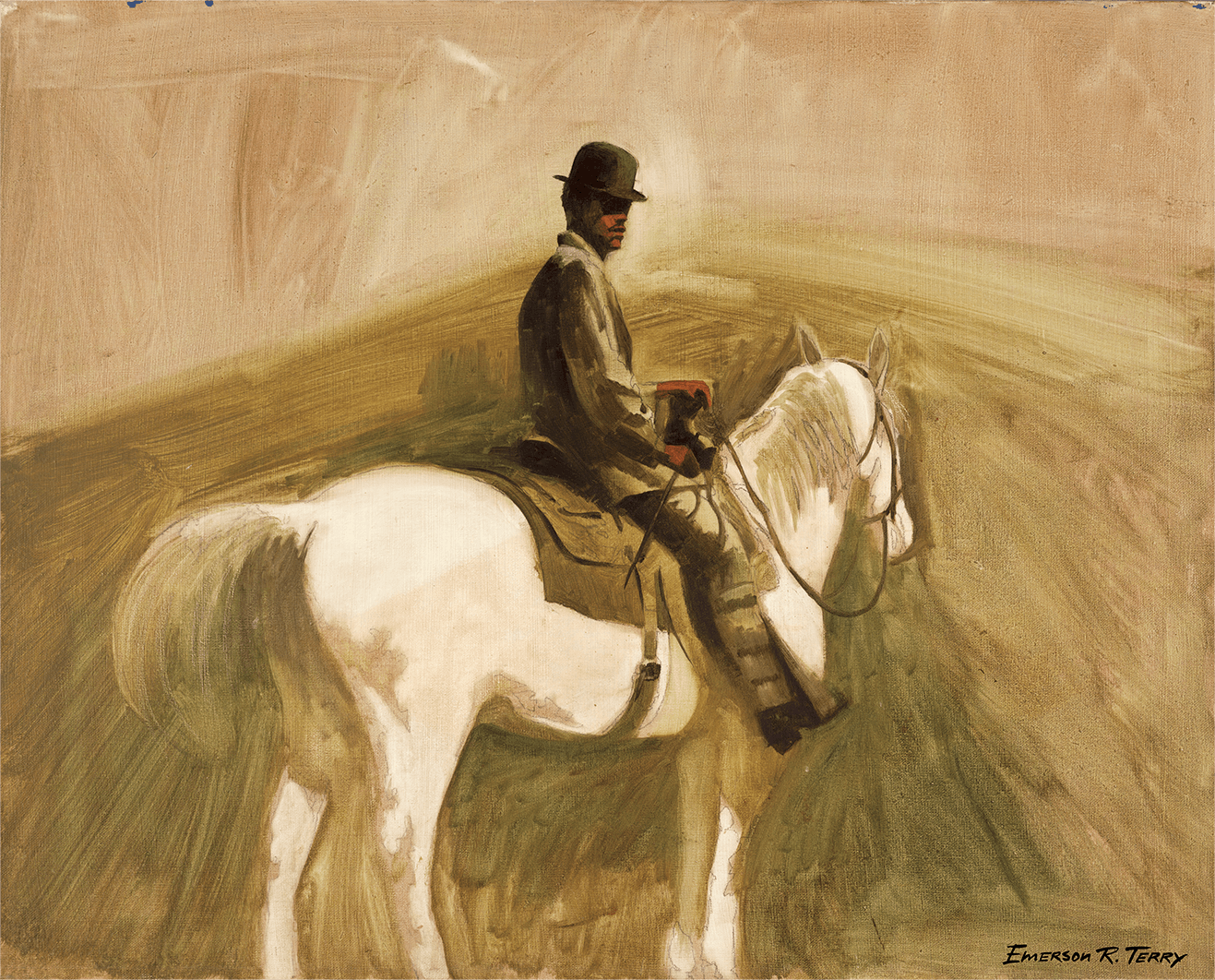

Nat Love guided his sorrel gelding up the last sandy rise before the gold-mad town of Deadwood came into view. The first shafts of dawn dazzled the tents and false-fronted saloons like hammered copper, but Nat’s eyes were on the open ground beyond space enough to rope a steer or outrun any man fool enough to challenge him. Born enslaved in Davidson County, Tennessee, he carried freedom in the set of his shoulders and the confidence of a bronc buster who had broken more horses than most foremen had ever owned. Tomorrow was the grand roping on the nation’s centennial, and Nat aimed to win it all.

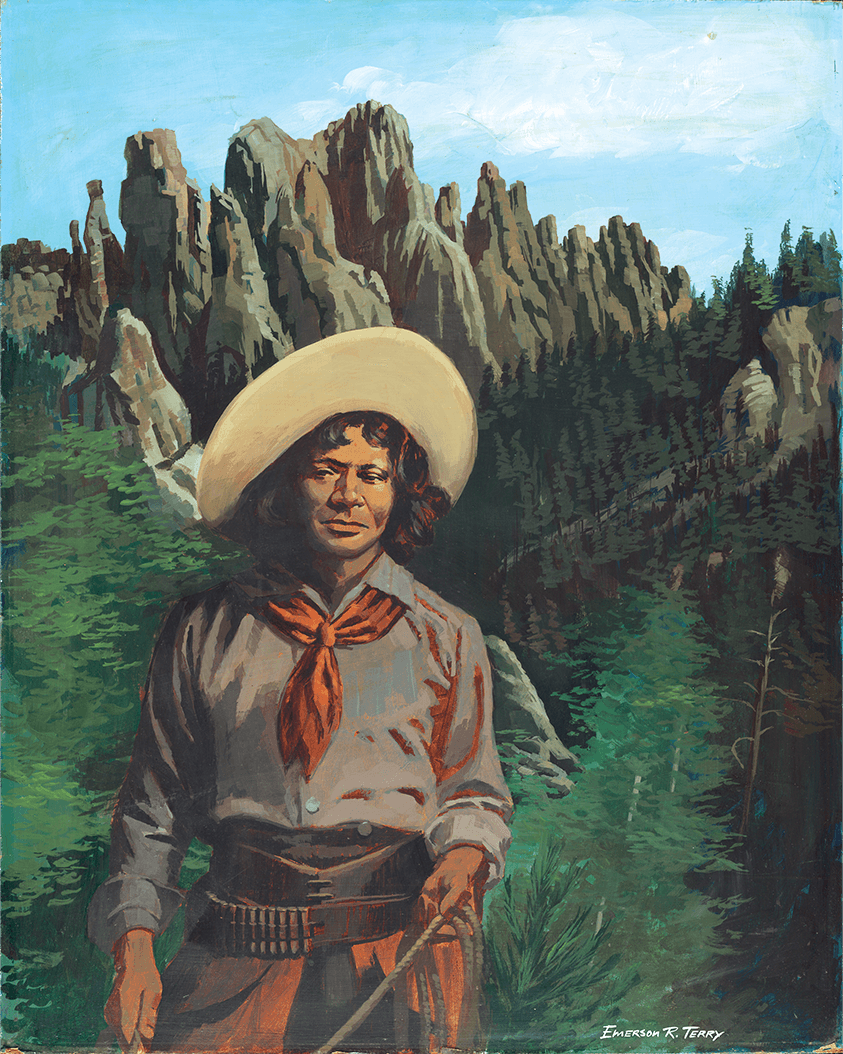

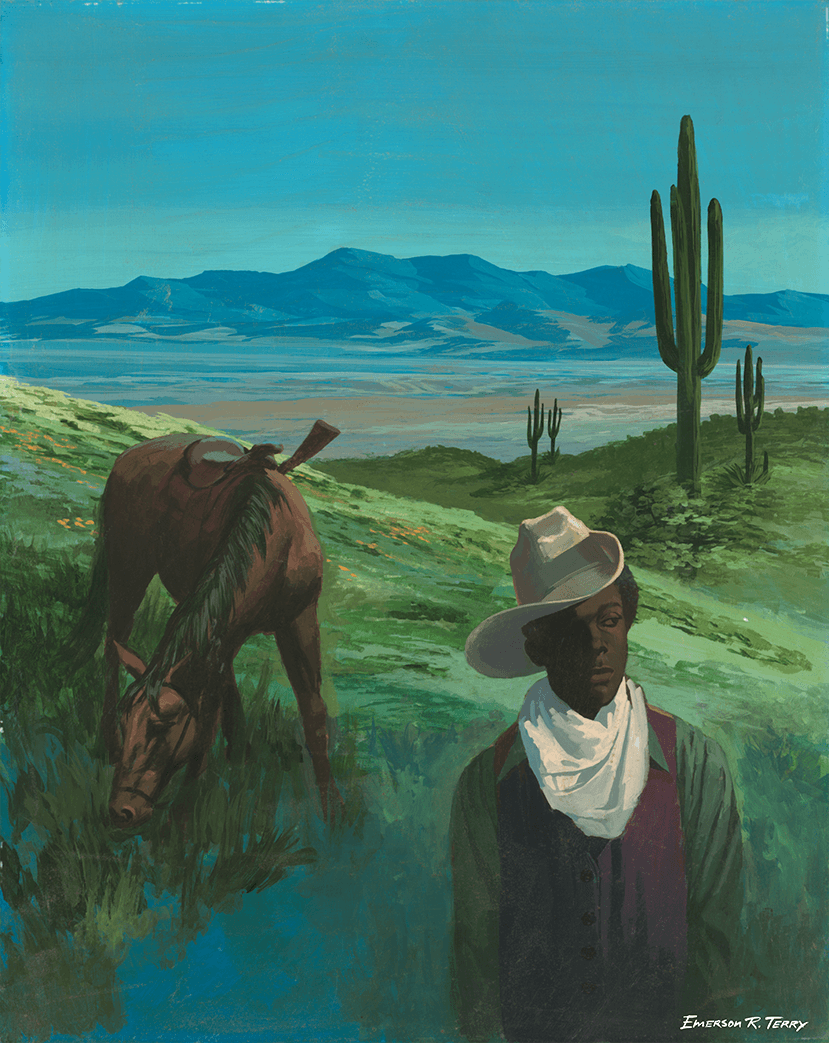

Down in the gulch miners in grubby flannels jostled Lakota traders and freemen hauling freight. By a corral near the Bella Union, Nat dismounted and dusted off his coat. A copper-skinned woman tended a dented coffee pot over a sheet-iron stove set on wagon wheels. Curls escaped her crimson pañuelo, framing eyes the color of mesquite bark.

“Morning, traveler,” she said, Spanish lilt braided with something older.

“Coffee’s two bits if you can wait for it to boil.”

“I can wait,”

Nat answered, tying his horse.

“Name’s Nat Love out of Texas cattle country. Folks call me Red River Nat, but I got room for new titles.”

She laughed, bright as spurs on flagstone.

“Catarina Valdez. My mother came north from Guerrero with camp laundresses when the Army pushed west, and my papa walked free out of Louisiana the night Union troops camped by the levee. I serve coffee and shade, sometimes news, always truth.”

“Truth is what I’m hunting. Heard Deadwood pays real money for a man who can rope wild and shoot straight. That so?”

A new voice, calm and iron-edged, carried from behind him.

“Money’s the least of it. You’ll want friends and a head on your shoulders.”

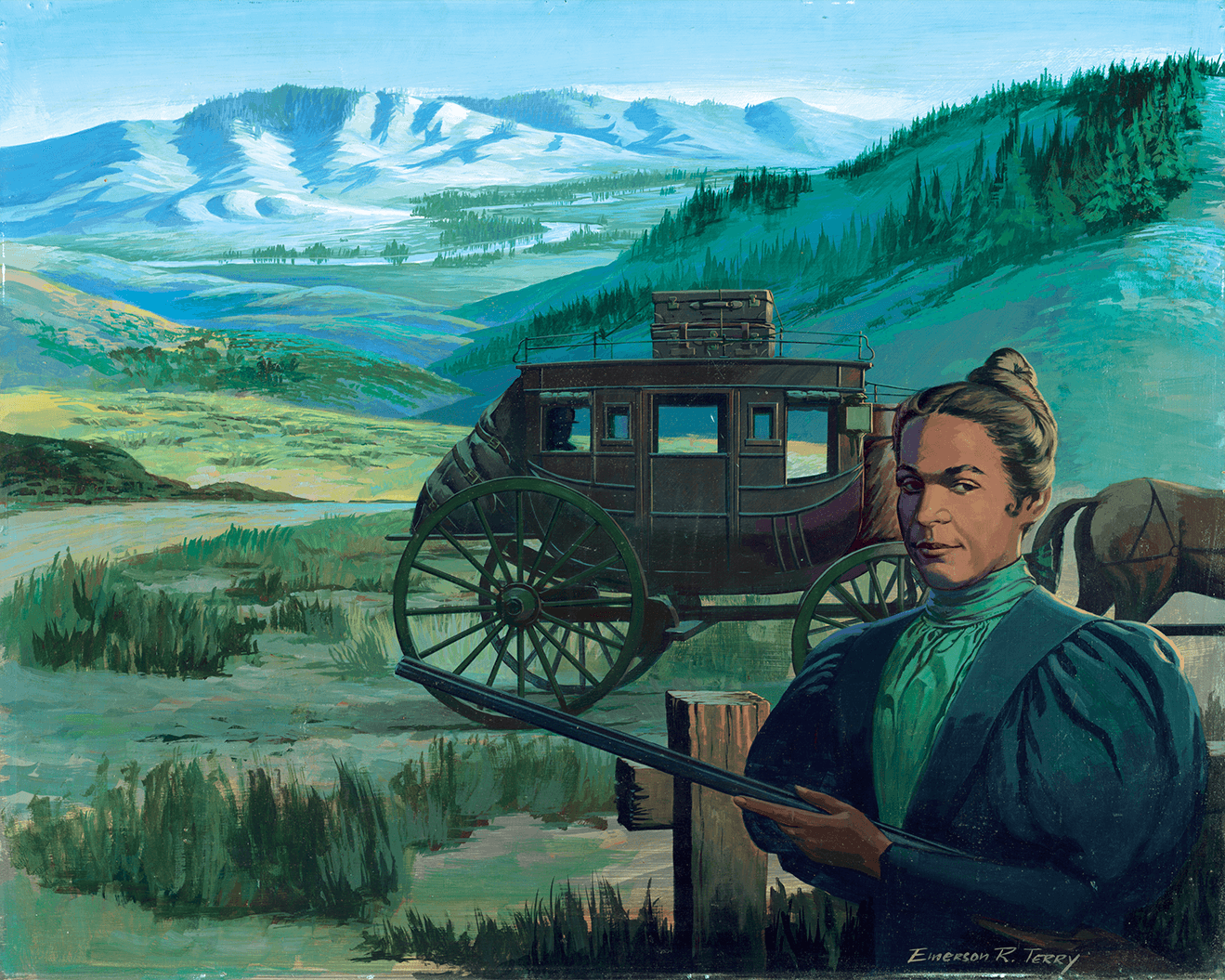

Nat turned to find a broad-shouldered Black woman in a plain work dress with flour on the sleeve, a canvas apron tied tight, eyes steady as an anvil. She balanced a lantern and a small ledger, like both light and accounts lived in her hands.

“You must be the roper stirring up talk,” she said.

“I’m Sarah Campbell. Folks here call me Aunt Sally. I cook when I must, dig when I can, and mind my business always.” She looked him up and down and made a small approving sound.

“Business today is telling you the hill’s full of drifters measuring you by color they don’t understand.”

Nat tipped his hat. “Then I’m obliged for the truth, ma’am.”

Catarina poured him a tin cup, eyes amused.

“Aunt Sally knows where every trail bends.”

❦

Deadwood’s main street rang with hammer blows on new plank sidewalks. Flags curled limp under the heat, stars looking down on a thousand hungry fortunes. At the livery, trick ropers warmed up by snatching hats off posts and hopping loops across running calves. Two white drovers noticed Nat’s dark face and sneered.

“Colored fella think he’ll out-rope us?” yelled the taller one, a blond with a scar twisting his lip.

“Bet my month’s pay he drops the slack before I count to three.”

Nat slid his rawhide glove snug.

“You got a name to attach to that bet?”

“Grady Milton.”

“I’ll remember it,” Nat said lightly.

“If you’re broke come tomorrow night, I’ll buy you a plate of beans.”

The crowd hooted. Grady spat.

“We’ll see how cocky you sound when my loop’s tight around your pride.”

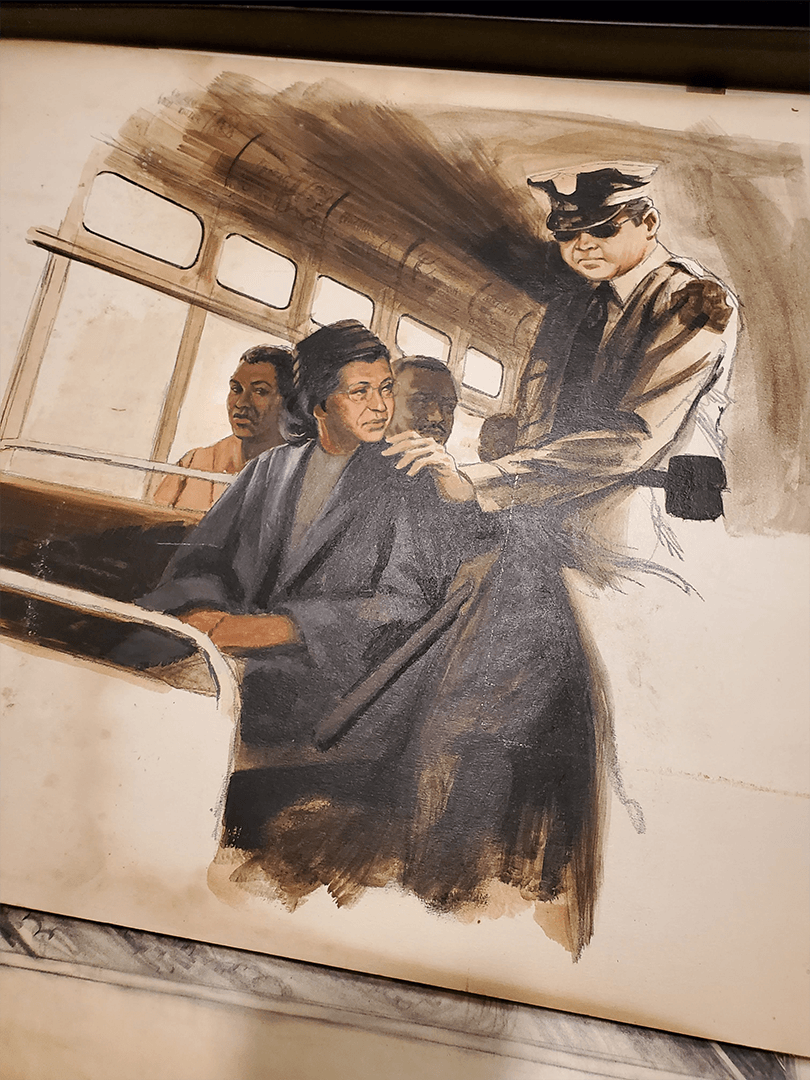

Before Nat could answer, Sarah stepped between them, lantern hooked in one hand, the other palm-up like she was setting down a skillet.

“Boy,” she said to Grady without raising her voice,

“Deadwood got laws and eyes. You’ll either use your rope on a steer tomorrow, or you’ll spend tonight explaining your mouth to the marshal. Which suits you?”

Grady’s pals tugged his sleeve, muttering about odds and spare brass. He backed off with a glare. Sarah nodded once, a smith satisfied with a true strike.

“Silence a fool before he convinces the world he’s wise,” she said to Nat, and moved on, ledger already open.

Catarina’s grin was quick.

“See? Lantern and a ledger. Light and accounts.”

“Remind me to stay square on both,” Nat said.

❦

Dusk brought a makeshift bandstand and cornet tunes. Catarina ladled chili and fry bread from her canvas stall, flicking ash from her stove whenever drunks grew grabby. Nat ate standing, savoring cumin under heat.

“Ain’t many women running outfits here,” he observed.

She shrugged.

“The plains don’t hand protection to brown girls.” Her gaze flicked to the Colt Navy at his hip.

“You any good?”

“Good enough to walk away breathing. But I came for roping. Shooting’s only insurance.”

Catarina’s voice softened.

“My aunt says a rope’s an umbilical a line to ancestors. You handling it tomorrow honors riders who broke earth under Spanish brands and American whips.”

He felt a stirring in his chest at that, a vision of a different West where Black and brown stories braided like rawhide and held.

“After the contest,”

he said,

“walk a spell with me? Teach me those old stories.”

“Win, and I’ll show you Fremont Gulch at moonrise. Lose, and I’ll still pour consolation coffee.”

“Either way, tomorrow can’t come quick enough.”

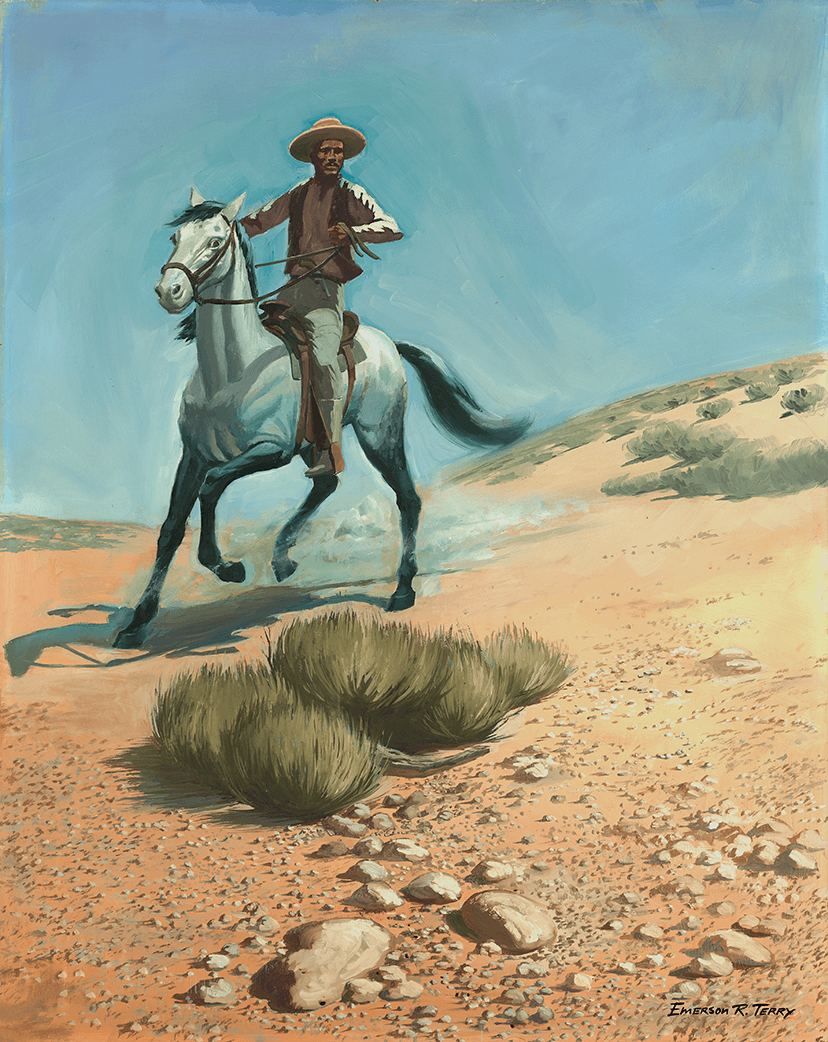

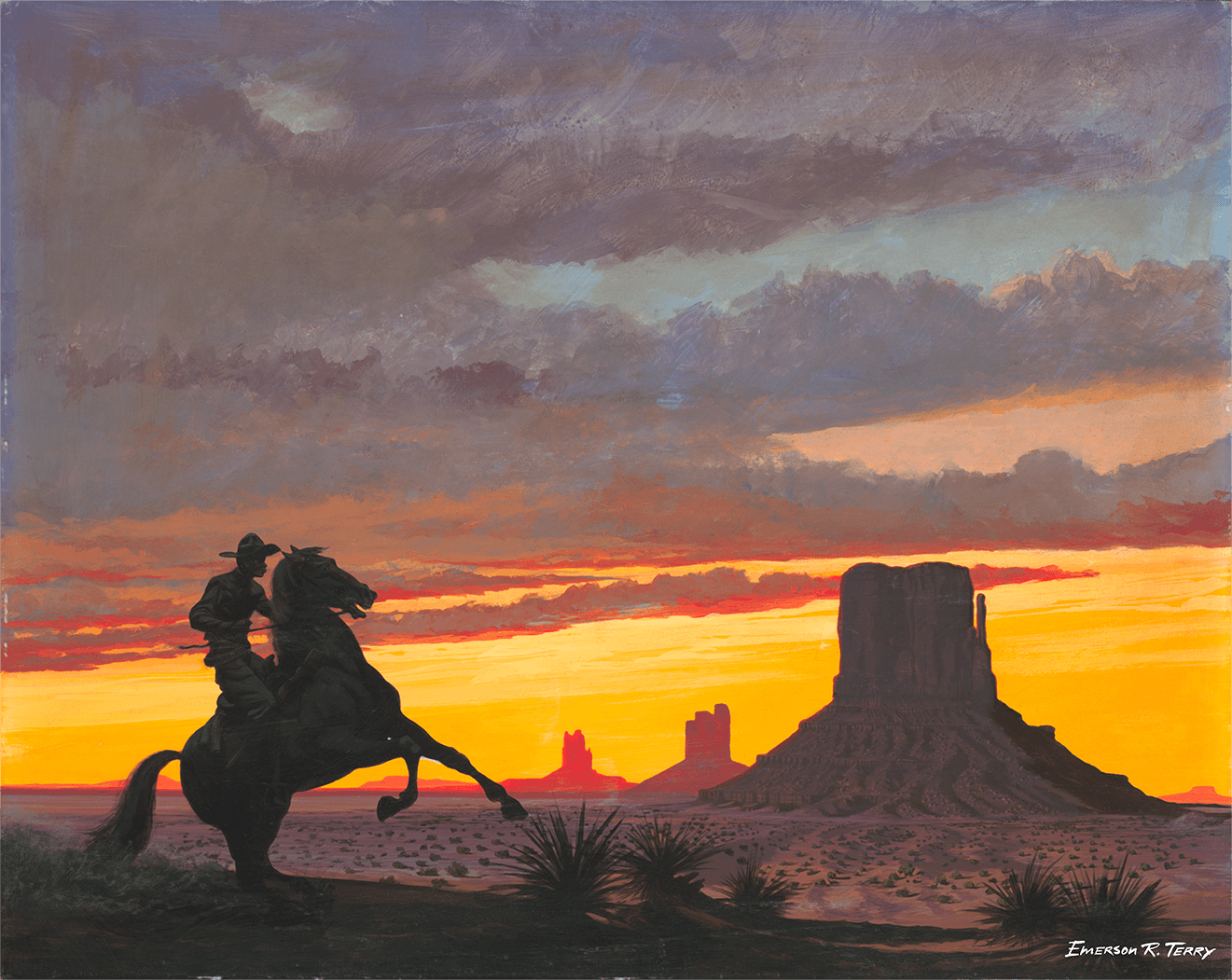

July 4 rose on rolling thunderheads, but by noon sun burned them away. The main corral thronged with spectators miners on sluice boxes, Lakota children perched in cottonwoods, gamblers stacking silver at a rough-hewn table. A timekeeper on a crate raised a blue bandanna.

“First round: rope, throw, and tie,” someone shouted.

A gate clanged and a mottled steer burst free. Nat’s arm moved like water; his loop sailed, kissed horns, cinched. The sorrel braked, dirt spraying. Nat vaulted, twisted the head, wrapped legs, and hawked the last half-hitch. He didn’t hear the time. He saw Catarina pumping her fist along the fence.

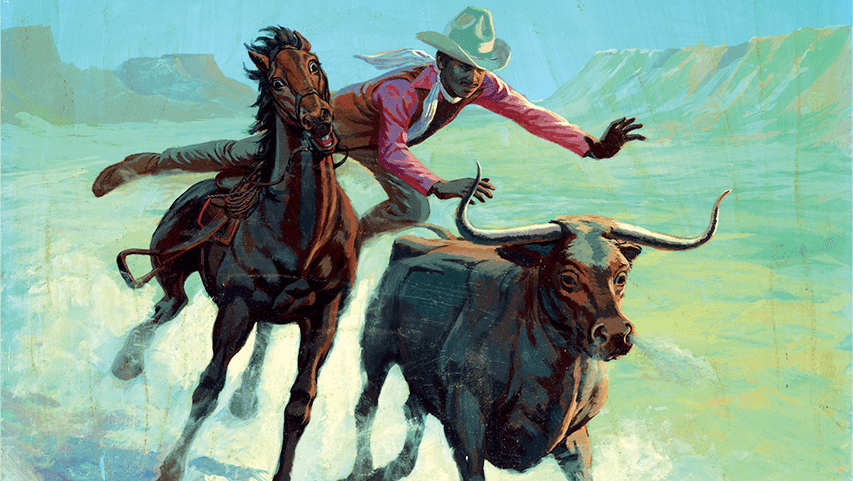

Second round: bulldogging. Grady’s steer veered; he leapt and skidded face-first. Nat’s steer juked left; he swung down, boots skimming dust, legs locking the shaggy head. With a heave the animal flipped, hooves churning air.

Final round called for a wild-horse catch and saddle. Wranglers cracked gates. A paint mustang shot forth, eyes rolling. Nat’s lariat arced; the mustang ducked. Gasps. He re-coiled, spurred, felt distance the way a hawk tastes thermals. He cast again; the rope settled neat as a chapel bell. The sorrel pivoted, dragging slack. Nat dropped, blind-looped a half-hitch over muzzle, then swung into bare back, settling blanket and latigo as the animal crow-hopped. Moments later the mustang froze, sides heaving, broken but unbowed.

“Champion!” someone roared.

“That’s Deadwood Dick!”

Coins rained. Pistols barked skyward. Powder smoke sweetened the air. The nickname stuck like pitch on a boot heel: Deadwood Dick, as if the dime-novel hero had stepped off a cheap-paper page and put on Nat Love’s skin. Nat breathed sap and sulfur and felt tides of history in his blood chains snapped, trails ridden, futures unrolled.

❦

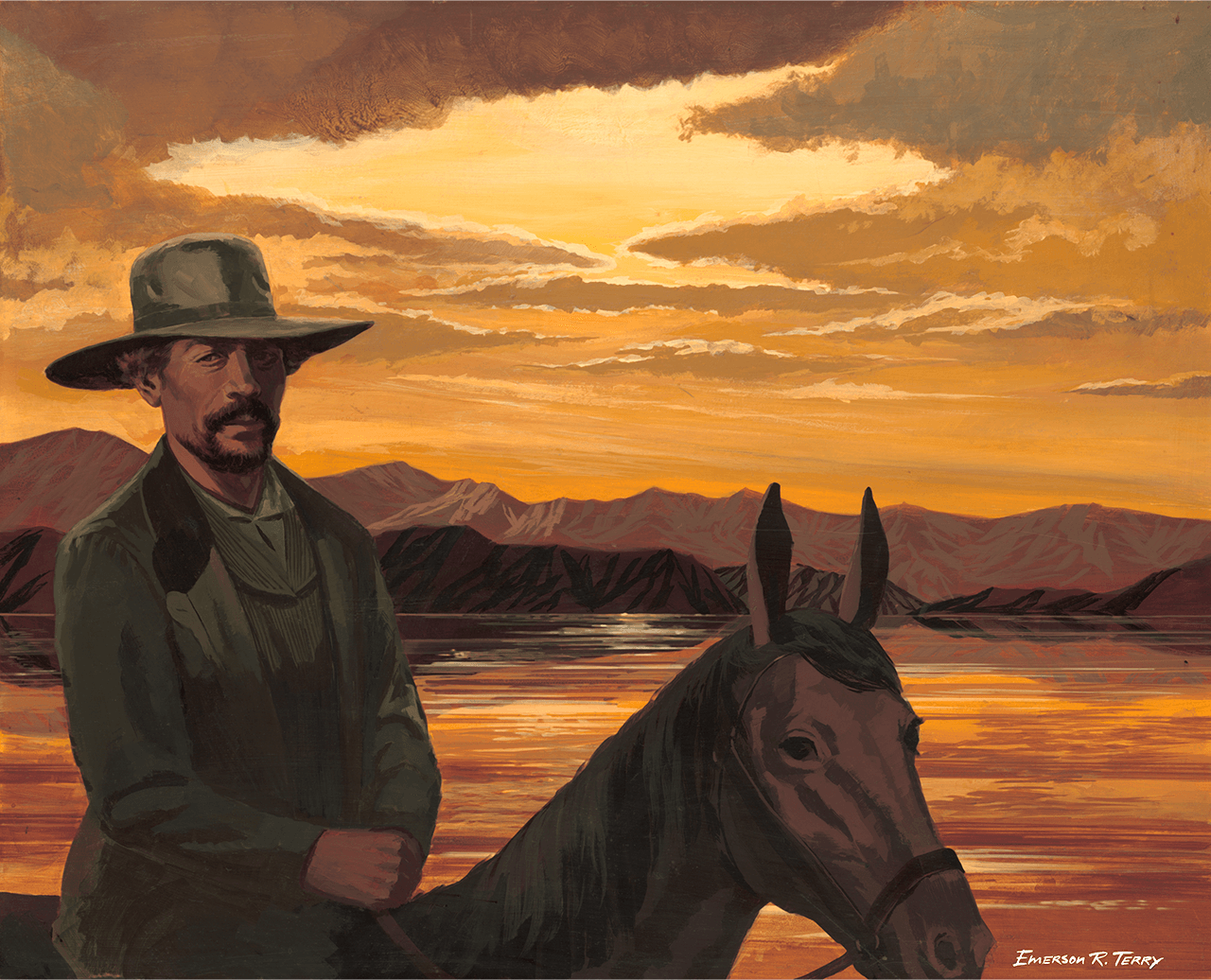

Lanterns glowed amber. Catarina led Nat through pines toward Fremont Gulch, where quartz veins glittered like spilled salt. Far off, a drum thumped from a ridge, answering the town’s ragged fireworks.

She stopped at a flat boulder ringed by sage.

“This is where I come to remember,” she said.

“My mother would whisper to the night: ‘Give me dreams brighter than bullets.’”

“Strong words,” Nat murmured.

“Stronger revolutions.” She traced a finger over his rope-scarred palm.

“Every loop you threw proved we survive systems set to erase us.”

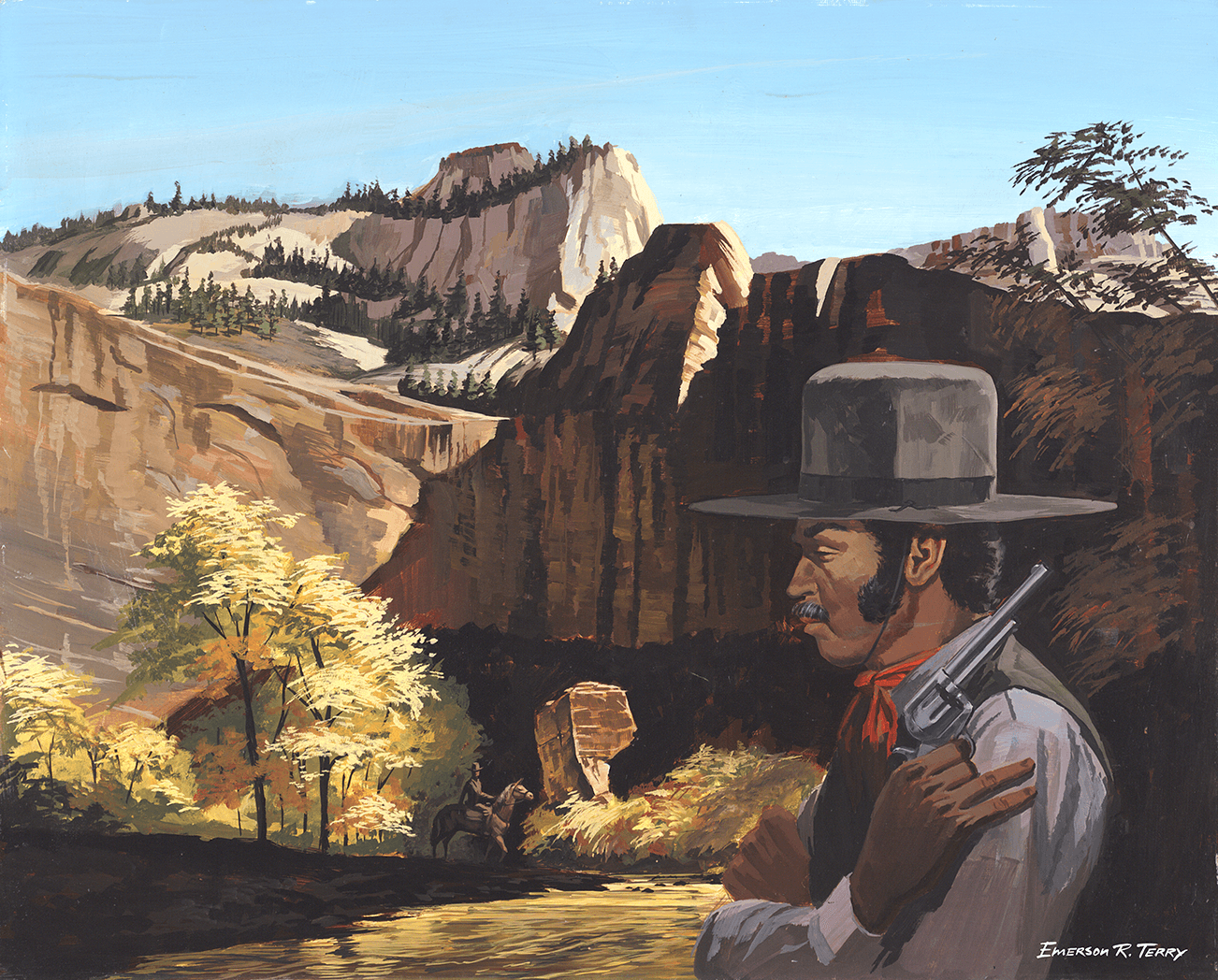

A twig snapped. Shadows shifted by the spruce. Grady Milton stepped out with two men, guns low.

“Well, Deadwood Dick,” he drawled. “Won yourself silver and a name and a pretty mestiza trinket. Hand over the purse and we’ll let you breathe.”

Nat pushed Catarina behind him.

“Three pistols to my one. Odds still feel unfair to you.”

“Drop it, Rooster,” Grady said, cocking the hammer.

A lantern bobbed through the trees.

“That’s enough foolishness,” called Sarah Campbell, apron dusted with quartz and flour, a half-dozen teamsters striding at her shoulders. She planted the lantern on a boulder like starting Sunday service.

“You boys looking to spend Independence Day in the lockup?”

Grady blinked at the sight of familiar men closing ranks around Sarah. The teamsters fanned wide, hands on ax handles and bridles, ordinary tools turned into warning.

“Mr. Love is a guest in this gulch,” Sarah said, voice low but iron,

“and Miss Valdez is under my protection, same as any woman who works honest. You can put those toys away and walk, or test whether Deadwood will bury you as cowards.”

One of Grady’s partners lost nerve first; his pistol dipped, then vanished into his coat. The other stepped back into shadow. Grady’s jaw worked. He spat, backed away, and melted into the pines.

The night breathed again. Crickets restarted their thin music.

Catarina exhaled shakily.

“Gracias.”

Sarah tipped her chin.

“This town remembers who stands up and who skulks. You two walk on. I’ll see you home.”

Nat swallowed. “I owe you.”

“You owe the people coming after you,” Sarah said.

“Win a purse, don’t just spend it. Build something white mouths can’t talk out of existence.”

“What would you build?”

“A place where riders of every shade can stable a horse and keep their dignity. Livery today, cattle tomorrow, wood camp next winter. Diversify.” She smiled a little, practical and proud.

“It’s how a woman like me lasts.”

Weeks later a lean-to had become Black Rose Livery, named for Catarina’s mother whose courage smelled of roses even when the Chihuahua Trail cut her feet. Catarina kept the ledger and the coffee hot; Nat shod mustangs that only his calm hands could soothe. Sarah came by with news and advice—where freight wagons would need fresh hay, which claims were played out, which fence lines needed mending before snow. She traded beef from a ranch outside Galena for nails and salt, always turning one revenue stream into two.

On an August evening the sky bled violet. Horses nickered; the scent of chili tangled with sweet hay. Catarina tucked the day’s receipts into a tin strongbox.

“Tomorrow the printer sets your story,” she said.

“People will

read ‘Deadwood Dick rides for freedom.’”

Nat chuckled.

“I told him my name is Nat Love.”

“Names evolve,” she replied, brushing dust from his shoulder.

“Spirits stay true.”

“My spirit’s stronger since you tied your story to mine.”

She smiled. “Rope’s an umbilical, remember? We’re braided to ancestors and futures both.”

Sarah stepped up behind them, lantern throwing a warm ring.

“You two are doing it right,” she said.

“Set the table, make room, insist on payment, and don’t let anyone steal your light.”

Nat leaned on the rail.

“What about enemies circling back?”

Sarah looked toward the dark pines.

“They will. But the hills carry memory. When honest people stand together, trouble learns to take the long way around.”

From the bunkhouse, a tired hand began a work song, a shuffling cadence turned soft as prayer. Sarah hummed in harmony, voice deep as creek-bed stone. The notes folded into the night until even the wind kept time. Nat closed his eyes and saw distant campfires ancestors nodding approval across mountains and years.

“Tomorrow brings more trails,” he said softly when the song faded.

“More contests, maybe danger.”

Catarina’s hand found his.

“And more coffee.”

Sarah’s smile creased her cheeks.

“And more ledgers balanced in our favor.”

Stars pricked the sky, hard and bright. The Black Hills held their breath, listening as a livery, a coffee stall, and an iron-willed prospector stitched a small, stubborn future Black, brown, and unbowed into a land that had never expected them to last.

Sarah “Aunt Sally” Campbell is historically documented in the Black Hills/Deadwood–Galena orbit as a cook, prospector, claim holder, rancher, and entrepreneur; her arrival traces to Custer’s 1874 expedition, with later returns and property near Galena. The story’s interventions and dialogue are dramatized; the roles (community authority, business savvy, diversified income) reflect documented patterns.

More Chapters