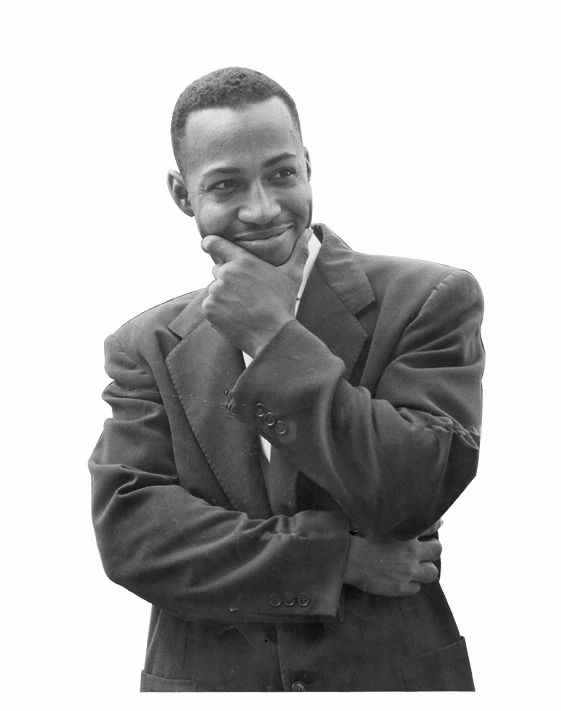

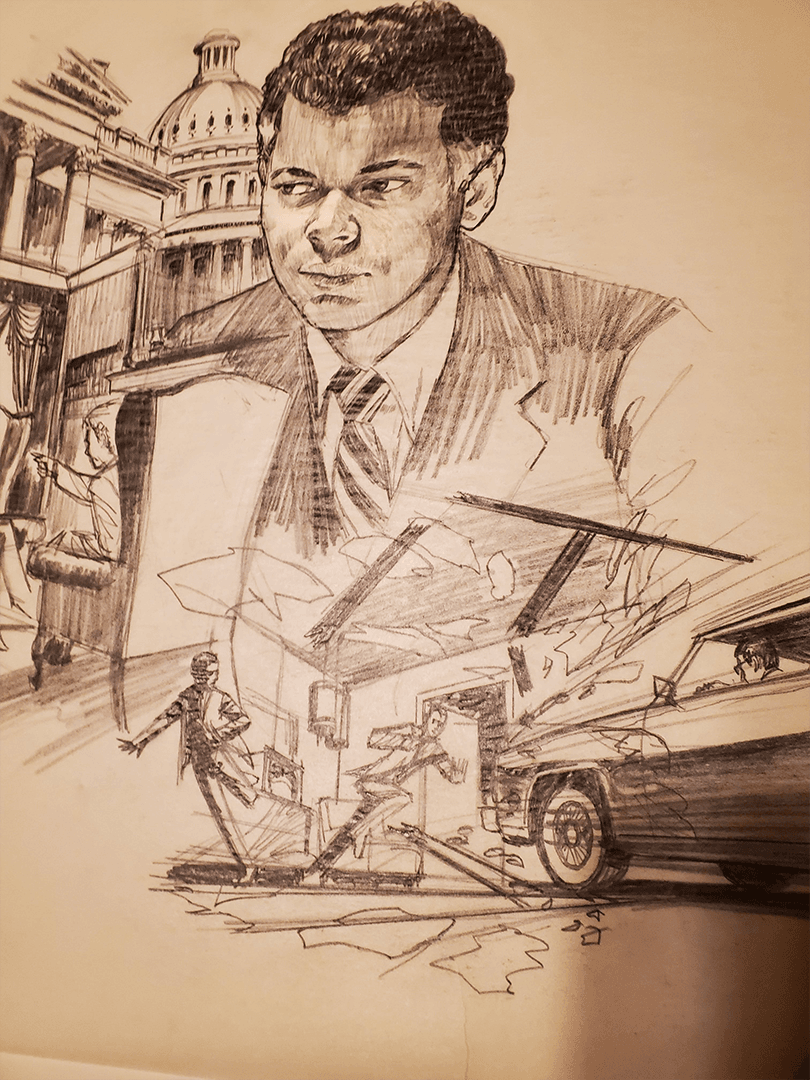

Terry and his friend Bill Moffet were two of the first students of African descent at Art College Center of Design. Moffet once told Emerson that when he, Moffet, applied for entrance to the College, the President of the institution, Tink Adams, said he could admit the black GI to his fledgling institution, but what would he do with the training? Moffett, Terry, and a few Mexican and Japanese students with GI Bills in hand were admitted into the school. The question that Tink Addams raised was still waiting outside the walls of the idealistic program. Whether in Detroit or Los Angeles, the answer for Terry and his fellow students was, NO, they would not be hired.

Terry had learned when he and his brother were very young children during the depression when you got to survive; you find a way. The Terry boys collected leftover fruit from train boxcars and sold it dirt cheap to their neighbors in Columbus, Ohio. As GI’s in post-war Los Angeles, the Terry brothers carried a ladder and painted signs on the windows of local businesses. There was and is to this day for Emerson Terry, always another way.

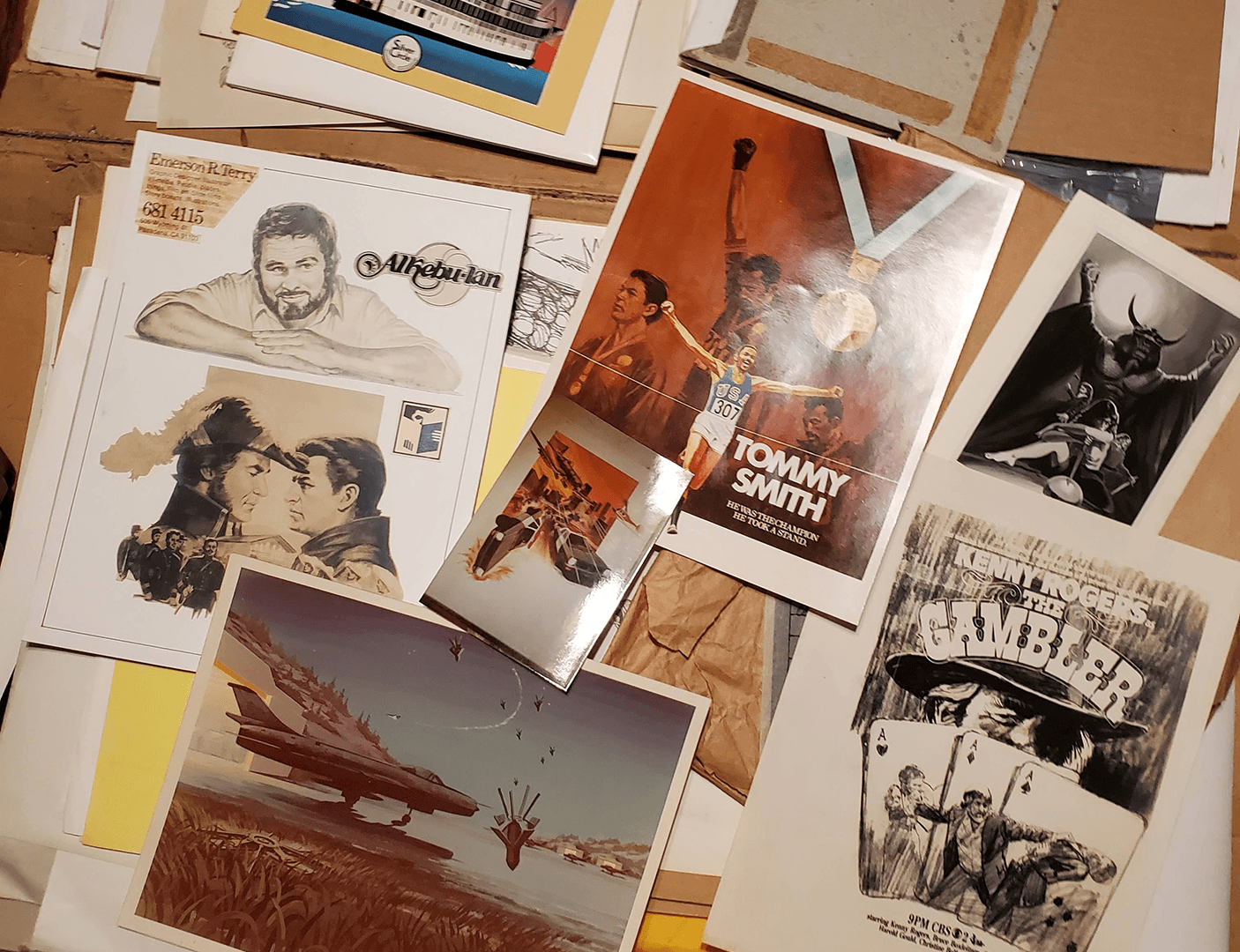

Jered Gold wrote about Emerson Terry in the February 15, 2012 blog post for Art Center’s “Dotted Line” online magazine,

“(Terry) is particularly proud that both his daughters have successful careers in art and design. ‘I was able to guide both of my daughters through some of the doors that I had to break down on my way up. Of course, I didn’t realize I was breaking down doors at the time. I just wanted to find a job as an artist.’”

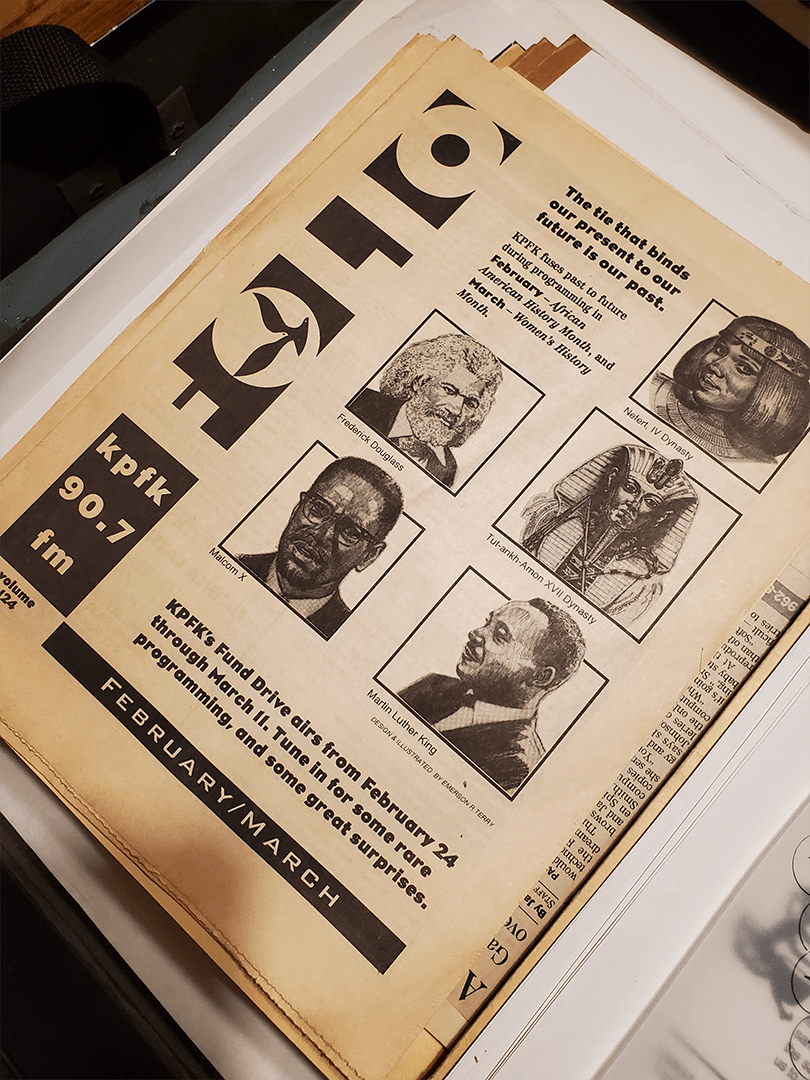

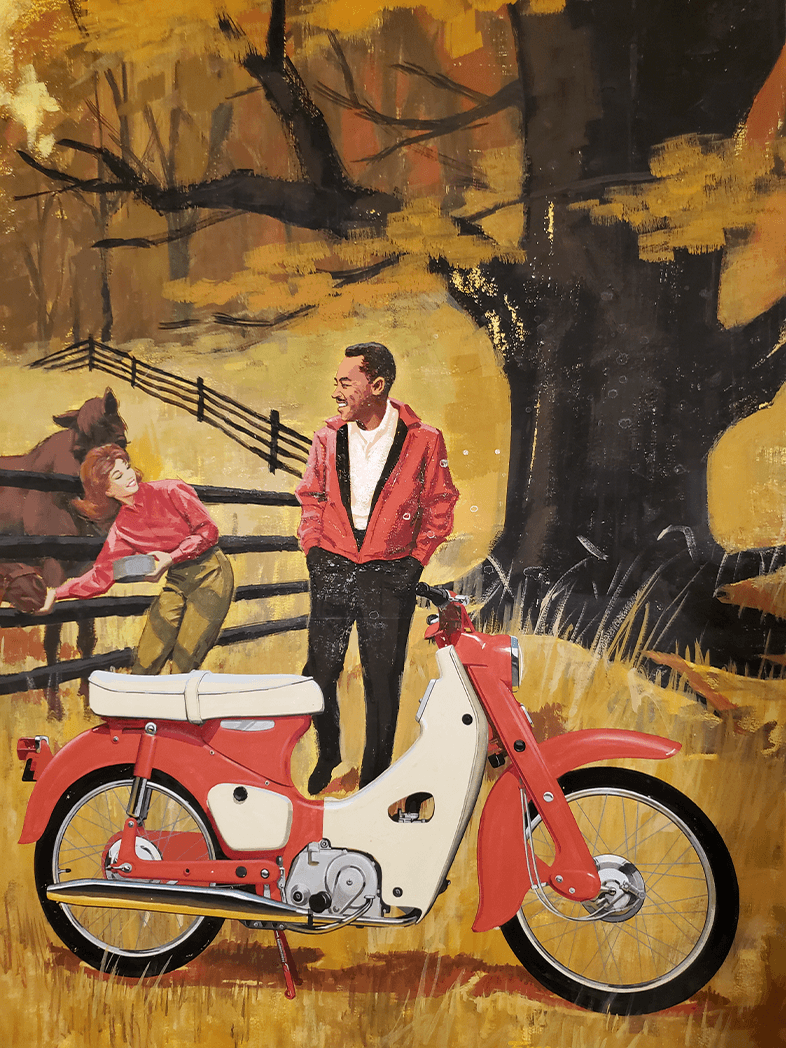

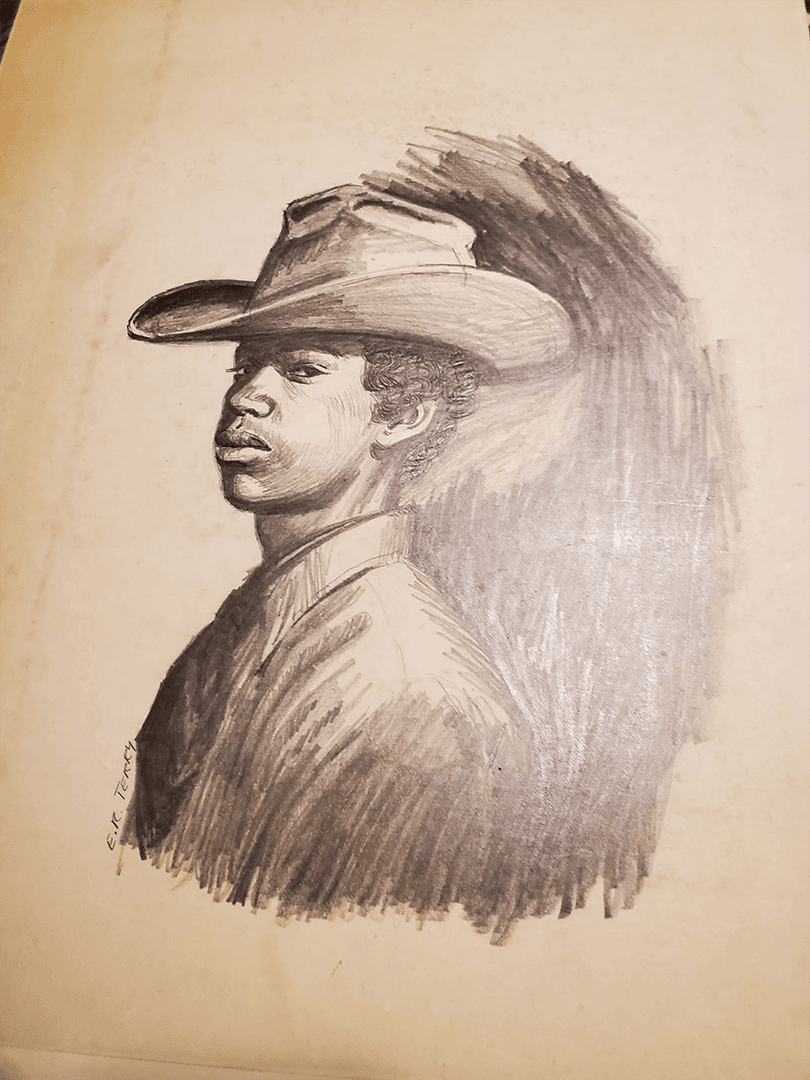

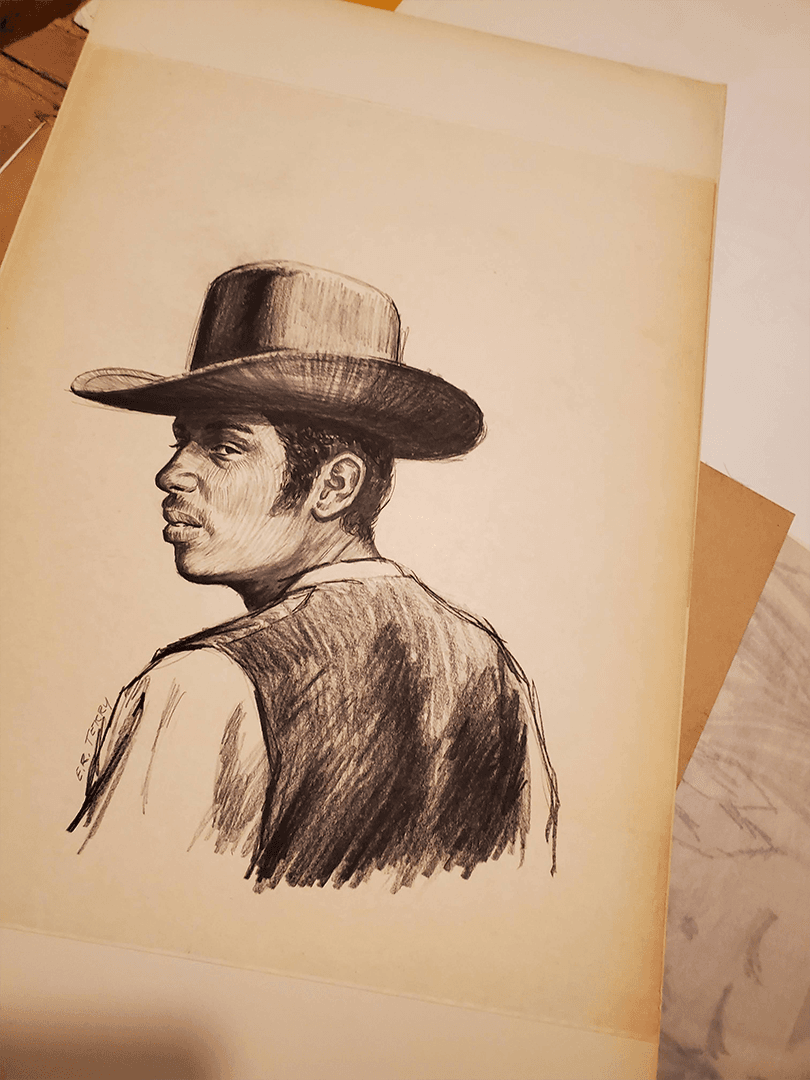

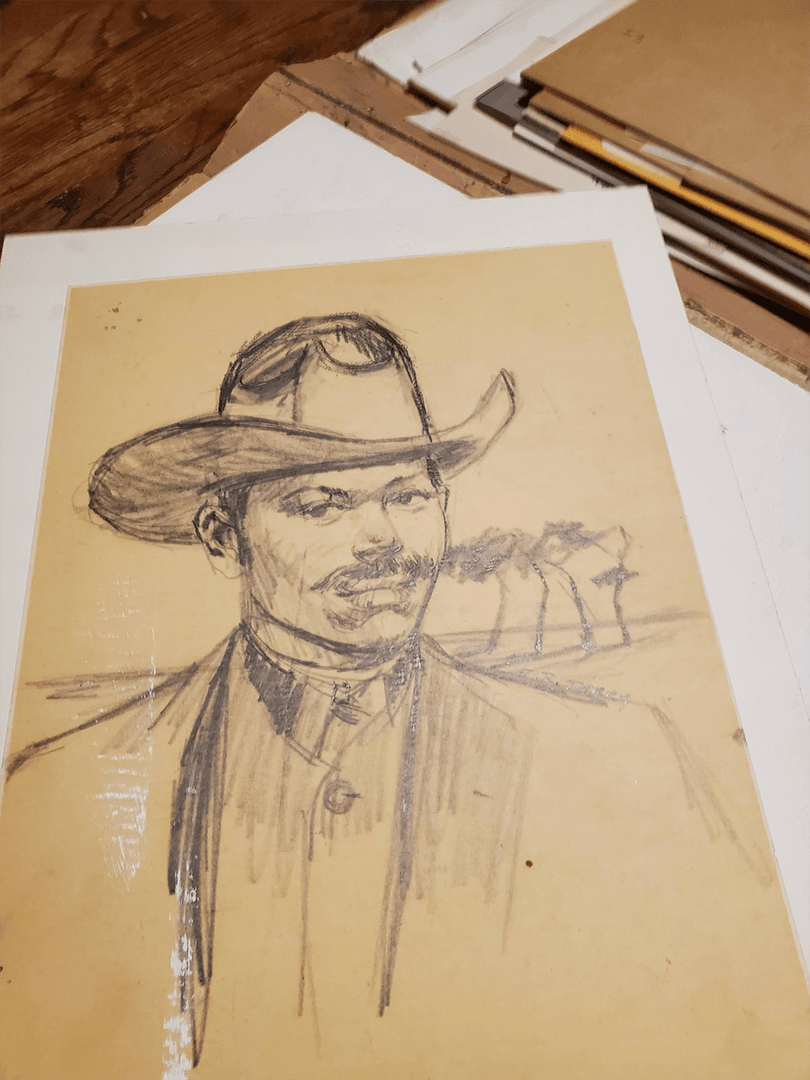

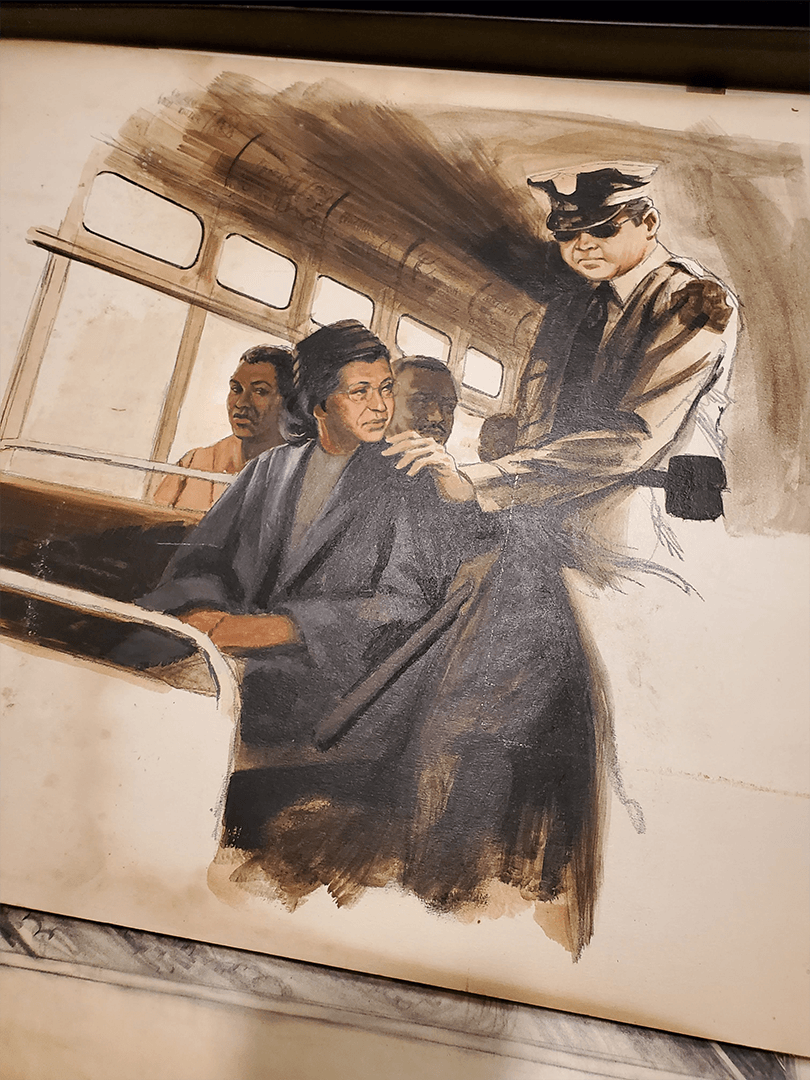

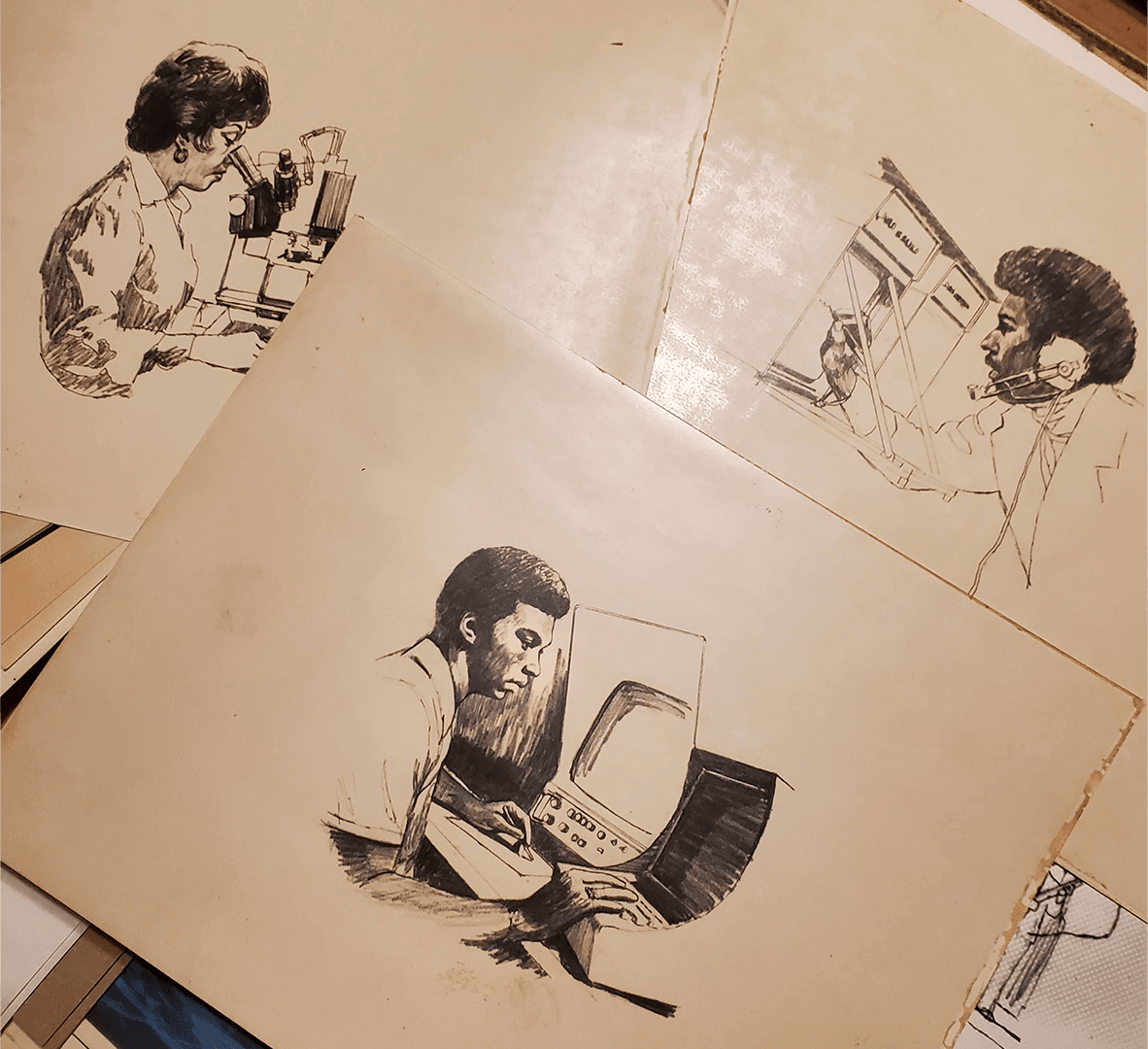

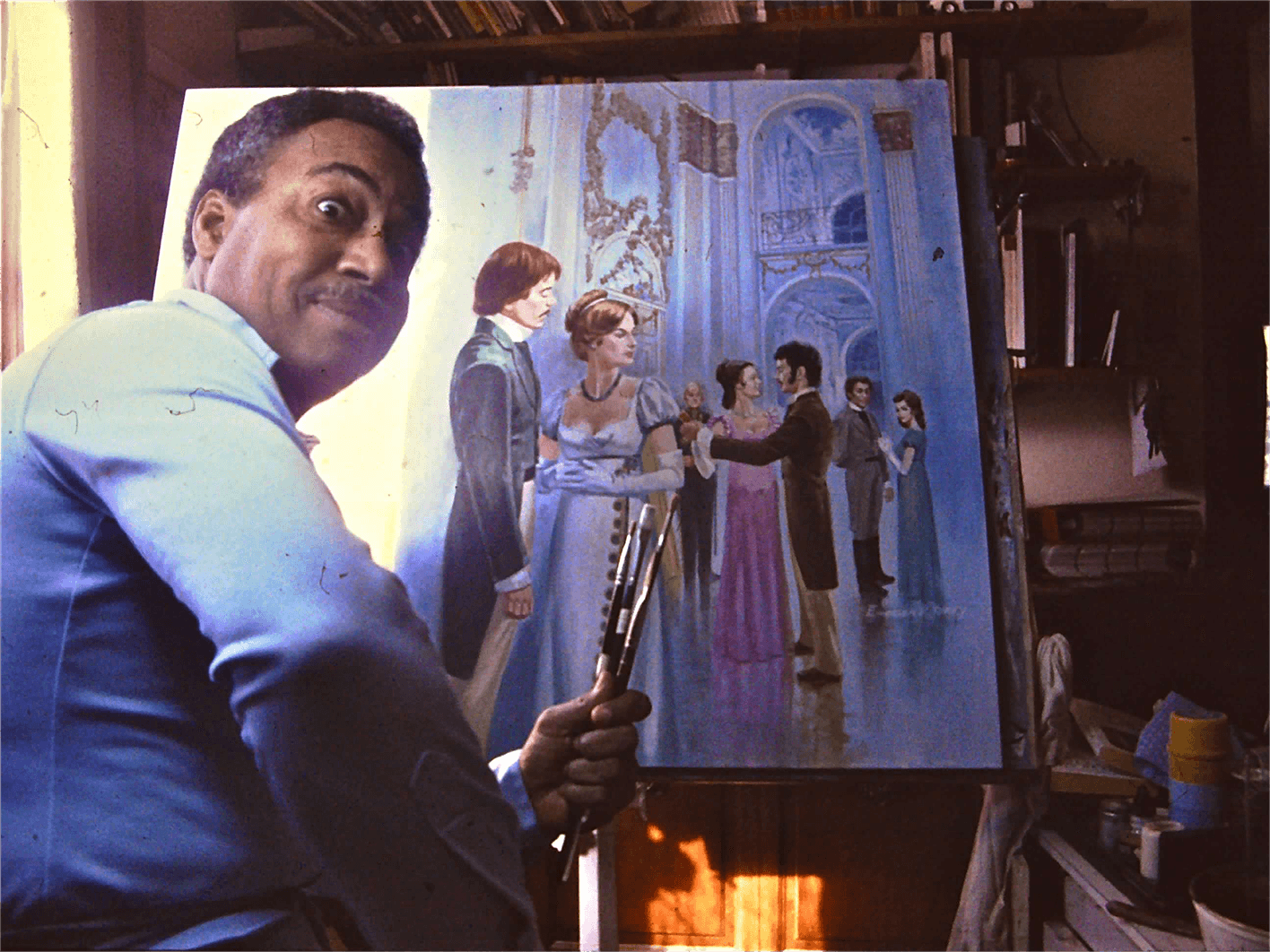

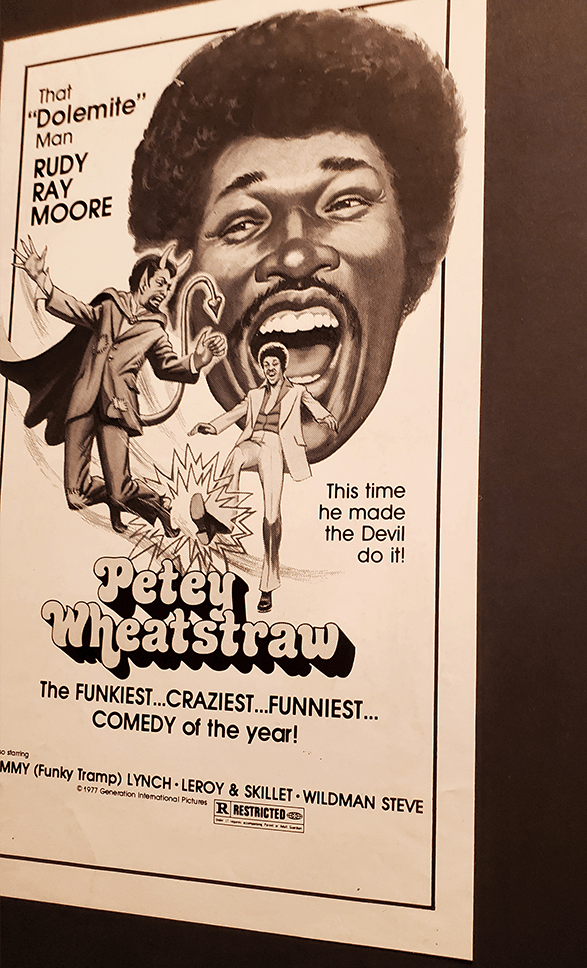

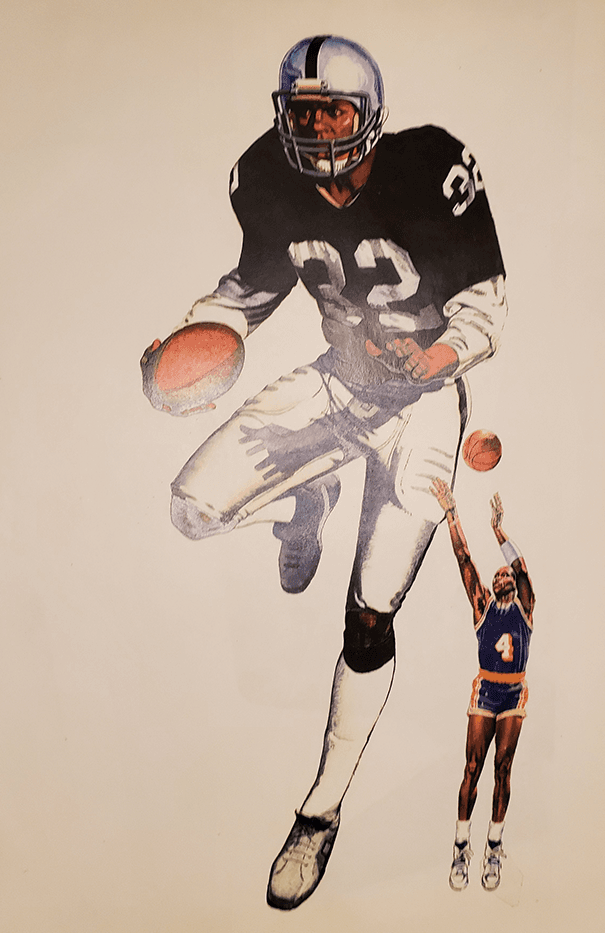

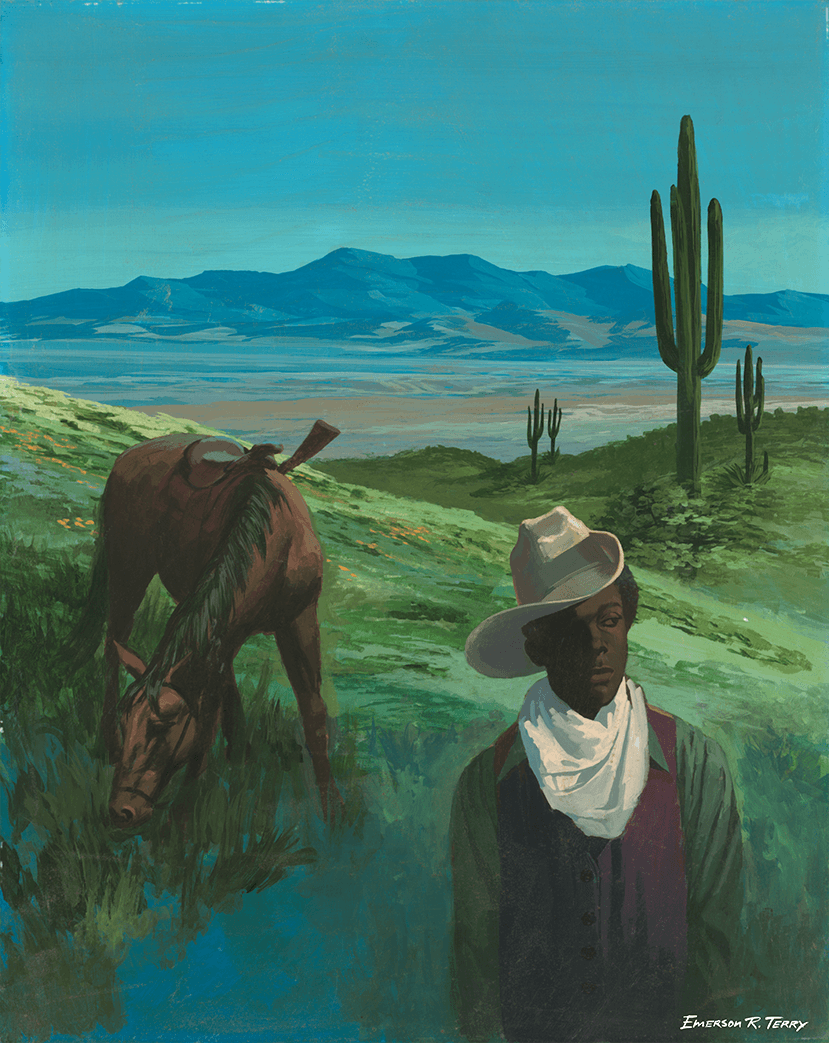

Even as a commercial artist, Terry pushed at the doors of inclusion by using family members as models for his work and including other people of color in his commercial artwork.